The verb ‘to hedge’ derives from the noun ‘hedge’ – that is, a fence or boundary formed by closely growing bushes or shrubs. Sadly (for gardening enthusiasts) this is not an instruction in horticulture.

Hedge has been used as a verb in the English language since the 16th century, with the meaning to ‘avoid commitment’. Even if you’re new to the world of finance, it’s likely you’ve heard the phrase ‘hedge your bets’ or ‘hedging a bet’ at some point in your life. Both phrases have been in circulation for centuries. Its first recorded usage dates as far back as the 17th century!

Whether you know it or not, most have likely engaged in the practice of hedging. A basic example of this is car insurance. If you have an accident, car insurance helps protect you against financial loss. It is a contract between the car owner and the insurance company. You agree to pay a premium and the insurance company agrees to pay for your losses, if any should occur. Another everyday hedge is life insurance. You purchase life insurance to support your family in the case of your death.

Insurance and hedging both reduce exposure to financial risk, though in different ways. Insurance typically involves paying someone else to bear risk, while hedging involves drawing up an investment that offsets risk.

Buying an insurance policy that protects your home against fire does not guarantee your home won’t burn down. Having car insurance doesn’t mean you won’t crash your car, and life insurance certainly won’t keep you from dying. Insurance simply shifts risk from you to someone else.

While protecting loved ones and possessions is vital, so is the ability to protect your finances! Sadly, the latter is often overlooked.

Financial hedging

It’s a fact of life markets fluctuate. Occasionally, though, markets experience bouts of extreme volatility and declines that can wreak havoc on portfolios. It’s easy to ride out minor fluctuations given a long-term horizon. But with rare large declines there’s something to be said for having a bit of protection – either for peace of mind or for performance.

Financial risk management is used to reduce the probability or degree of financial loss in the face of uncertainty. Its basic principles involve recognizing and measuring the financial risk of an existing position, and entering a new position with opposite exposure such that the gains and losses of the positions cancel each other out.

So, in effect, hedging is the transfer of risk without purchasing insurance policies. Hedging employs various techniques, offering wide-ranging levels of complexity. Forwards, futures, options, swaps, credit derivatives and the spot market are common investment vehicles used to hedge a position.

Hedging strategies

Nobody knows if a bull market will continue for another 20 years or crash tomorrow! Just as you need insurance for your car to protect yourself in the event of an accident, or home insurance in the event of a fire, investors, at times, also need to tend to their financial exposure. Although hedging is a mammoth subject, the following are some of the common strategies used in the markets today:

A forward contract is an agreement to purchase something on a future date at a specified price.

The forward market is an over-the-counter market for forward contracts that do not trade on an established exchange. It’s unlikely retail investors will engage with this market as contracts are generally undertaken by large investors and financial management institutions.

A simple example of where this type of investment vehicle may be used is to hedge exchange rate exposure:

Say a US tech company agrees to purchase 500,000 circuit boards from a South Korean Manufacturer in six months, at a per unit price of 24 won (KRW). At current price, the won-dollar exchange rate is 1,200, meaning $1 will buy 1,200 won. The total delivery price of 12,000,000 won will be $10,000 at the current exchange rate. To ‘fix’ the future price of the circuit boards in USD, the US tech company executes a forward contract to purchase 12,000,000 won for $10,000 in six months.

What the company did here was offset, or hedge, its exchange rate risk using a forward contract as it’s practically impossible to know where the exchange rate will be in six months’ time.

A futures contract is a standardised forward contract executed at an exchange. Much like a forward contract, a party agrees to either buy or sell an underlying commodity or security at a specified price on a stated date in the future.

Imagine you own a bread factory and plan on purchasing 50,000 bushels of wheat in six months and the company wants to lock in a price now. To offset its exposure of wheat prices, the company enters long (buys) 10 wheat futures contracts with a delivery price of $3. Each contract guarantees the delivery of 5,000 bushels of wheat in six months for $3 per bushel. The company expects to pay a net total price of $150,000 for its wheat. Six months later, the current spot price of wheat has risen by 50 cents to $3.50. The total value of the company’s futures position on 50,000 bushels has thus risen by $25,000. The company liquidates its futures position and buys 50,000 bushels from its regular supplier at $3.50, or $175,000 altogether. The net price, however, is $175,000 minus the $25,000 futures gain, or $150,000 as desired.

The foreign exchange (FX) spot market:

Nowadays, the majority of FX brokers allow hedging, unless you’re based in the US. Hedging was banned in 2009 by CFTC Chairman Gary Gensler for US-based FX brokers.

Folks stating hedging is a pointless activity in the spot market may not truly understand how the function operates, as it certainly has its uses.

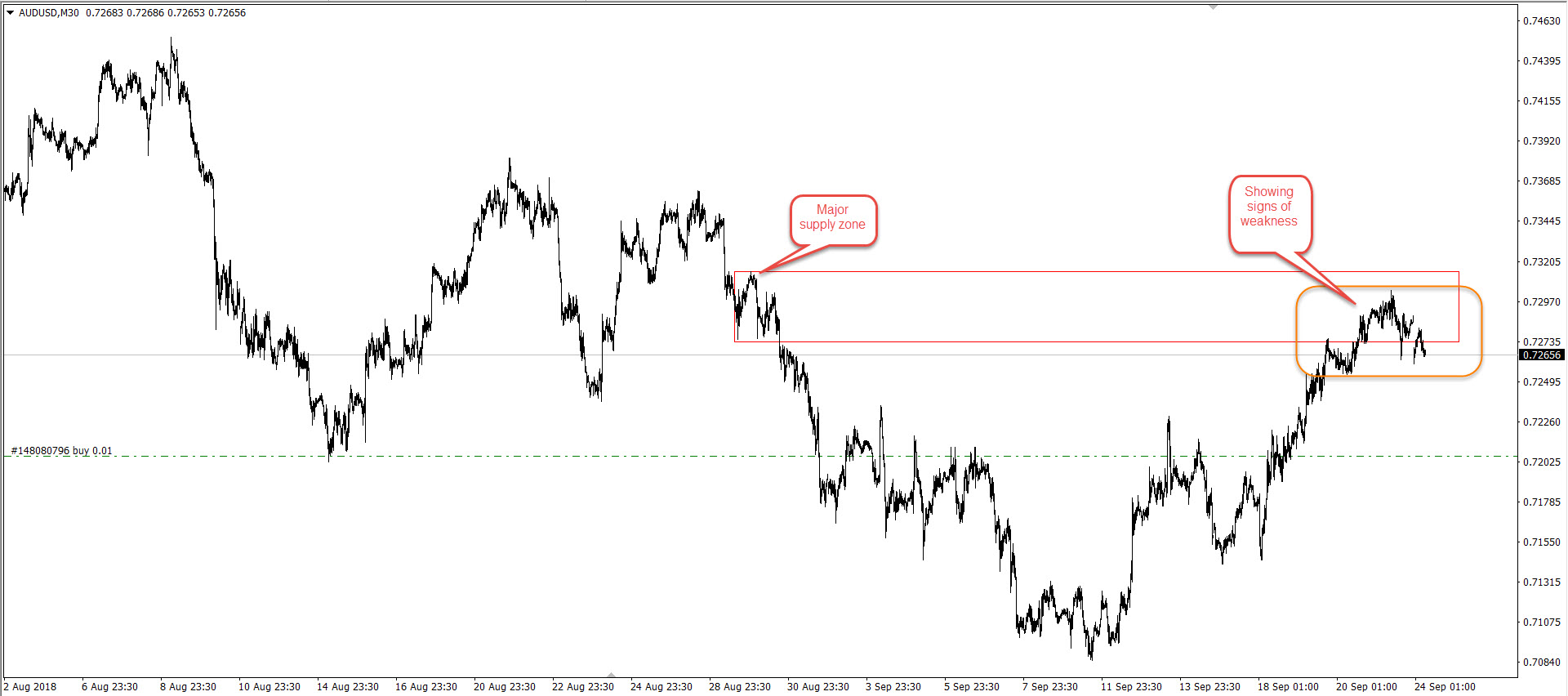

At its most basic, it can buy time. Imagine you’re long the AUD/USD currency pair and the market moved in favour quite substantially. Unfortunately, price has begun showing signs of topping around a major supply zone:

You could, of course, simply liquidate your position here and collect the profit.

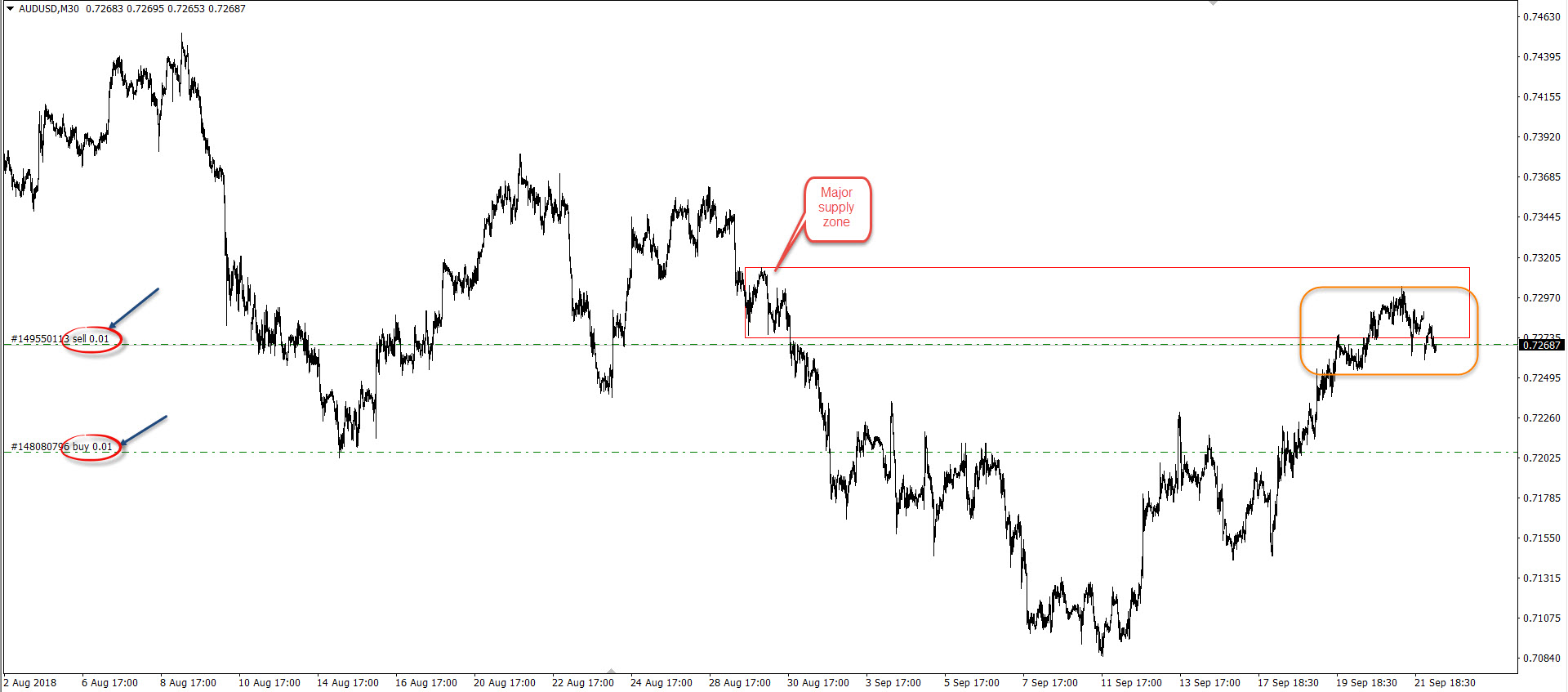

But what if your analysis calls for additional upside beyond the current supply base? Do you wait and just live in hope, or maybe take partial profits off the table? Fortunately, there’s an alternative: you can offset the risk at minimal cost by entering short (sell) at current price using the same position value as the long (0.01):

Minus the commissions on the short position, the sell has effectively locked in profit without closing the trade or moving the stop-loss order.

Should the market press lower and return to breakeven on the long position, the short trade (as above) will compensate for this loss and provide you with profit. In the event price action begins making headway above the current supply zone, nevertheless, removing the short position (the hedge) is then an option, allowing you to take part in any further gains the market may offer.

Final words

The world of hedging is vast, offering a plethora of techniques. Entire books are written on the subject! The objective of this article was merely an attempt to scratch its thick surface.

While some traders may never need to engage in hedging, it’s still a subject worth exploring and understanding, even on a basic level.

Remember, the art of investing or trading is never conquered – we’re all perpetual students of the game.